“Cogito Petrisséur”

Nature shapes blending into each other in this wood sculpture

When the self is kneaded with matter

Academic question: How can material experiences in a creative process based on flow elicit and communicate non-linguistic cognition

“Cogito petrisséur” is about "kneading" the self with the material - a kind of poetry of touch, like when an industrial worker uses his hands to grasp, rub, weld and shape. This project was to lead, through various creative exercises and strategies, to 2 finished "works" that were to be exhibited. I describe one of the works in this article. The other work will be described in a separate entry.

Flow and play became important tools. Flow occurs when you forget time and place and are just completely present in what you are doing. I experienced this when I stopped thinking about how something should look, and instead followed curiosity and sensory impressions.

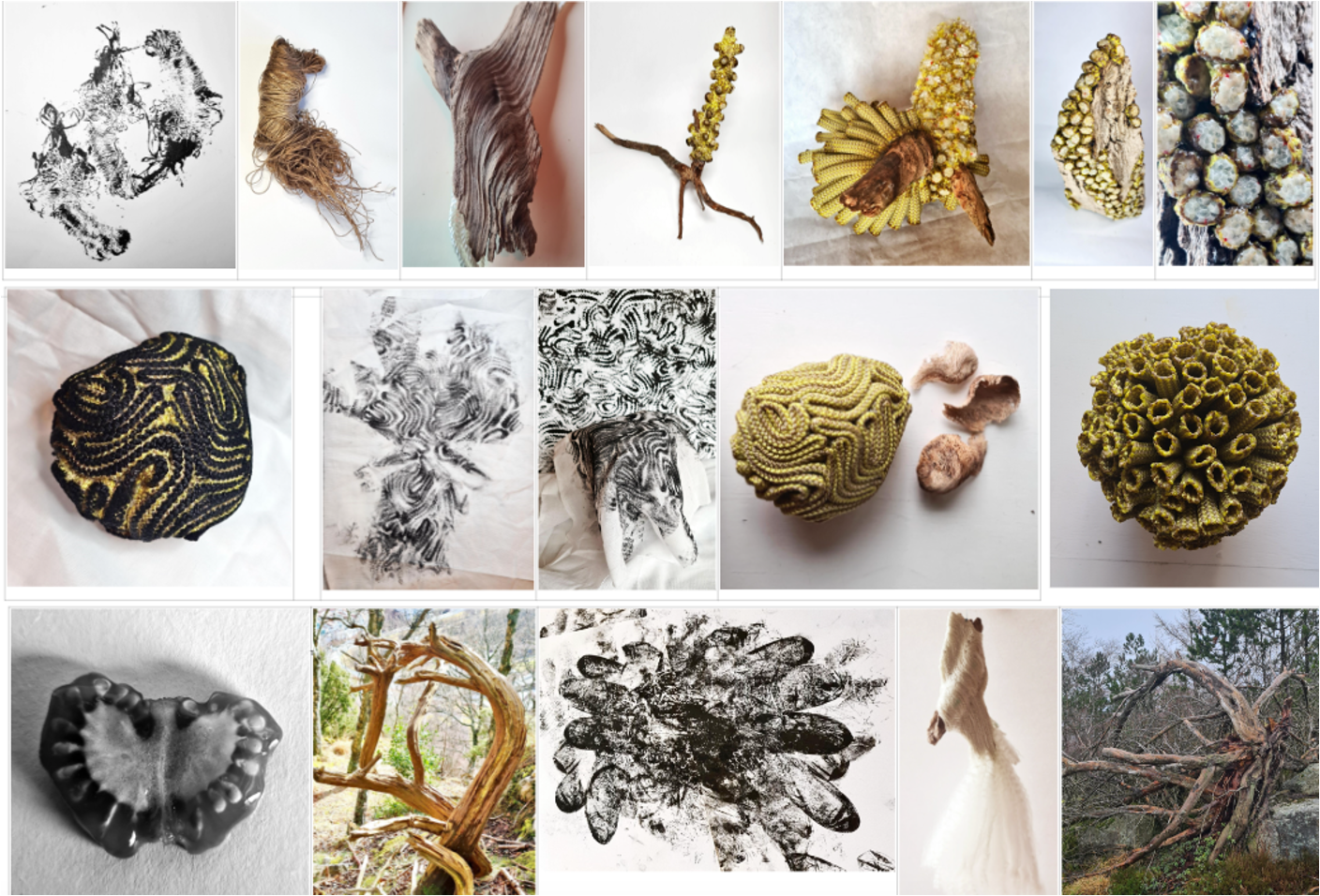

As a former mountaineer, I experienced the climbing rope as personally meaningful to work with as a material. I melted, cut and pressed it against different surfaces, and let the properties of the material guide the process. I developed a method where I alternated between creating 3D objects and 2D prints - a kind of dialogue between body, material and expression. This released performance anxiety and gave me a freer and more intuitive way of working.

Exploration of climbing rope

Through this process I gradually I noticed that my expressions had something both beautiful and disturbing about them. I connected it to bodily experiences of pain and vulnerability - and to the insight that we humans are also nature, matter and perishable. The artworks, which show ropes wrapped around stones and trees, can arouse wonder, recognition - or perhaps even discomfort - without needing to be "explained". The background was a personal experience: a fall in the mountains where I almost lost my left foot. Seeing my foot partially torn off made a strong impression. Through creative work with hands and materials, the expressions created a recognition and an opportunity to express and process this - not with words, but through form and feeling. Art became a way of understanding and sharing the ineffable.Philosophical Understanding of Matter

Dualistic Understanding

Philosopher, mathematician, and scientist René Descartes (1596–1650) distinguishes between thinking substance (res cogitans) and extended substance/matter (res extensa). In Descartes’ world, res extensa is synonymous with nature. The thinking subject (cogito) can understand matter separately from itself. Matter lacks an inner substance or existential depth; it is inactive and devoid of inherent vitality (Cool, 2010).

Phenomenological Understanding

This dualistic understanding of human beings and matter is challenged by phenomenological philosophy, which provides a doctrine of what appears to humans and allows us to describe the world instead of defining or explaining it (Austring & Sørensen, 2006). Austring and Sørensen reference philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s (1908–61) view of Descartes’ understanding of reality, calling it an artificial division. Everything is interwoven, he says—nature is matter, the body is nature, and consciousness has a bodily origin that introduces meaning or structure into matter, because the body is literally matter with the capacity for agency.

Agency can be defined as the ability for conscious action and choice based on free will (OpenAI, 2023). (Appendix 1). Phenomenology seeks to show how consciousness arises from, yet remains entangled with, the material world (Cool, 2010). Merleau-Ponty therefore emphasizes the human bodily and sensory foundation for experiencing the world and regards the artistic approach to the world as ideal for understanding reality. Based on this, sensory bodily information becomes primary, and reflection comes afterward (Austring & Sørensen, 2006).

Virtual Understanding

Researcher Lovise Søyland distinguishes between materie (matter) and materiale (material) (Søyland, 2021). In an aesthetic context, she describes materie as what something is made of, while materiale is what we make something with. In this light, I understand materie as, for example, what a stone is composed of, whereas materiale is the stone itself, which I can make something with.

Furthermore, Søyland describes virtual materiality as an illusion—a visual representation of physical materials made accessible through software in a digital technology. She points out that we receive multimodal experiences through all our senses and that the virtual’s limitation to sight and hearing therefore provides a thinner response and less sensory information. Based on this, understanding becomes dependent on previous bodily experiences.

I will now introduce aesthetic theory to compare understandings of matter with the subject through aesthetic activity.

Aesthetic Theory

Engaging with the World through Exploration and Play

Søyland describes play, action, and making as strategies for discovering new things, calling this exploration (Søyland, 2021). Exploration, she claims, can yield open-ended results, where the process—not necessarily the outcome—is the focus. It is not linear but spreads in different directions like a rhizome, a botanical term describing the underground stem of a plant (Aarnes, 2023). Explorations and ideas thus become like buds shooting in all directions, where one thing leads to another.

Austring and Sørensen argue that choices regarding motif, color, composition are not immediately conscious—but neither are they random. They are made through a long series of intuitive decisions (Austring & Sørensen, 2006). Aesthetic expressions are based on bodily and sensory experiences, and they argue that this meets the human need to communicate physical and emotional experiences and to see the world anew. Tacit knowledge about the most essential things in life can become visible to us in ways where discursive language falls short. The emotions that arise in an aesthetic process can be complex, contradictory, and unclear, but through aesthetic expression they can be explored and communicated. This offers the opportunity to connect with repressed emotions and experiences, to release and reconcile with them. To best communicate with others, we use a visual language that employs aesthetic tools linked to our senses (Mørch, 1994).

Colors and shapes express energy and can evoke many associations.

Mørch claims this can express emotional life and insights—a connection that can be difficult to explain, as it is first recognized after becoming an emotional experience. This illustrates an aesthetic process in which the self is allowed to emerge, revealing the communicative potential of aesthetics. Using the term cogito pétrisseur, I will provide further understanding of how this arises in the self’s encounter with matter.

Bachelard’s Cogito Pétrisseur

The French literary scholar and thinker Gaston Bachelard (1884–1962) was interested in how matter engages our imagination and mind (Gao, 2019). He claimed that in our waking fantasies or daydreams (from the English reveries), a cogito (a thinking subject) can emerge. Bachelard describes a cogito pétrisseur. Pétrisseur is French for kneading or molding. Bachelard’s cogito differs from Descartes’ cogito, which separates the self from matter.

In Bachelard, I understand the self as part of and fused with the world, and his cogito pétrisseur can thus be linked to phenomenological thinking. Bachelard distinguishes between formal and material imagination. Formal imagination comes from the person: from feelings and the heart, and is concerned with form, color, and surface. Material imagination, on the other hand, draws power from the material’s own substance. By entering into its depth and essence, it triggers an active imagination in which the subject can merge with both its pliancy and resistance.

Different types of matter engage the imagination and color our fantasies and dreams. Material imagination should be rooted in materials that invite touch and fusion with our soul, thoughts, and imagination. Bachelard argues that we must discover the poetry of touch, like the industrial worker who crushes, rubs, grips, strikes, and welds with hands that penetrate the material itself. Matter with an unfinished and undefined form (translated from the English paste) also frees, according to Bachelard, the artist’s concern with form and engages the material imagination rather than the formal.

Aesthetic Strategy and Analysis

The theory drawn upon to analyze my creative work is Kristine Harper’s conceptual pair Comfort booster/breaker, also called breaking the comfort zone (Harper, 2015). Harper claims we feel pleasure through recognition and identification in others’ aesthetic depictions. She draws on the term catharsis, which means that the audience can recognize and relive the emotions the artist has attempted to evoke—but from a safe distance and without having to experience them personally.

In this essay, I use this strategy to analyze the process, mindset, and the communicative potential of the work. According to Harper, elements that can be used in the comfort breaker strategy include, for example, the unexpected, which can play with the receiver’s connotations through a jumble of stories, often surreal. It can use defamiliarization or taboo subjects that both attract through form/color and repel through theme.

What is unexpected and what is familiar about things can be understood and challenged through analysis. Here, Bråten and Kvalbein’s analysis framework for object-things (Bråten and Kvalbein, 2014) can provide a basis for understanding, by breaking things down into smaller parts and perhaps contributing to seeing something new in what is familiar. In this way, it can offer a broader understanding of and contribution to the creative process and the possibilities for communication.

Sources:

Austring, B. D. & Sørensen, M. (2006) Æstetik og læring, Grundbog om estetiske læringsproseser. Hans Reitzels forlag.

Austring, B. D. & Sørensen, M. (2006) Æstetik og læring, Grundbog om estetiske læringsproseser. Hans Reitzels forlag.

Coole, D. (2010). «The Inertia of Matter and the Generativity of Flesh». I New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics, redigert av Diana Coole og Samantha Frost, 92-115. Durham: Duke University Press.

Gao, Y.,(2019) Between Matter and Hand: On Gaston Bachelard’s Theory of Material, Imagination, Journal of comparative literature and Aesthetics, Vol. 42, No. 1 (73-81) http://jcla.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/YANPING-GAO.pdf

Harper, K. (2015) Æstetisk bæredygtighed. Samfundslitteratur.DK

Hammervol, I. (2018, 16. november) Materialitetens tidsalder, Kunsthåndverk

http://www.kunsthandverk.no/anmeldelser/2018/11/16/materialitetens-tidsalder

Lappegard, H. Å. (2007, 1. august) Identitet og sted: En sammenligning av tre identitetsteorier, Psykologitidsskriftet. https://psykologtidsskriftet.no/fra-praksis/2007/08/identitet-og-sted-en-sammenligning-av-tre-identitetsteorier

Mørch, A. (1994) Form og bilde, Kompendium. Telemark lærerhøgskole

OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (4.mai versjon) [Stor språkmodell]. https://chat.openai.com/

Skjerdingstad, K. I. (2012). Det fenomenologiske blikket - et materialistisk perspektiv, R. Audunson (Red.). Krysspeilinger: Perspektiver på bibliotek- og informasjonsvitenskap. Oslo: ABM-media. s. 65-88, hentet fra https://hdl.handle.net/10642/1061

Svartdal, F., (2020) Flyt. Hentet 9.mai 2023 fra https://snl.no/flyt_-_psykologi

Søyland, L. (2021). Grasping materialities: Making sense through explorative touch interactions with materials and digital technologies (Doktorgradsavhandling,

Universitetet I Sør-Øst Norge). USN Open Archive. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2756969

Ulekleiv, L. (2020, 28. Mai) Materialets kraft, Norsk kunstårbok https://www.kunstaarbok.no/arrangements/article.php?id=164

Vyro (u.å). Imagine (1) [AI art generator]. Google store. Hentet 2. April 2023 fra https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.vyroai.aiart&hl=en&gl=US